Tom's GUIDE to more memorable creative

Before I go further, I just want to reorder an important summary of advertising principles that Tom provides in his article. Simply re-ordering his five principles gives us a nice little acronym: GUIDE.

Get attention fast

Use stories to communicate (and use new arcs)

Integrate brand/product

Difference works best

Evoke intense emotion

If nothing else, this reordering makes the principles easier to remember. And, although I am very tempted to add an S for "Specific to context," for once, I'm going to leave well alone.

These principles are not ground-breaking

To my mind there is a fundamental dilemma implicit in Tom's article. He states,

"None of these principles is ground-breaking, in fact they should be meat and drink to all creative people."

I agree. These principles are not ground-breaking. They have been known for decades, and that leads to the question of why they have not been adopted on a more consistent basis.

While Tom couched these principles in the context of digital advertising, I cannot see any reason why they would not apply to traditional TV advertising. Yes, the "lean-back" nature of TV might give the advertiser a little more time to develop their storyline, but honestly, I think the contrast between traditional and emerging story arcs is a bit of a red herring. An ad that gets attention fast is one that is off to a good start, no matter what media channel or platform it is used on.

Stop the scroll!

I agree that stopping the scroll is mission critical when it comes to infeed advertising, and that what will work best will differ by the platform in which the advertising will appear. However, stopping the scroll has proven to be a big challenge, and not because of shorter attention spans. Tom highlights research by Karen Nelson-Field that finds that 85% of digital ad views fail to achieve a threshold of 2.5 seconds of active attention.

Honestly, that finding does not seem surprising. Almost every day I scroll past ads placed prominently in the New York Times and LinkedIn, very few capture my attention for more time than is necessary to assess my likely interest in what they have to say or show. Most of the time, I do not even stop scrolling, as I seek something of more interest. Ad avoidance has become an instinctive behavior.

The real challenge is to hold attention

For the record, our attention is always on, so the real challenge is to escalate and sustain attention. Humans have evolved to automatically attend to what is going on around us and anticipate whether it is worth devoting more attention to a specific item, event, or ad. The real challenge is not to get attention, it is to intensify and prolong attention to a point at which people have processed the content extensively enough for an impression to enter long-term memory.

Different media context, different duration

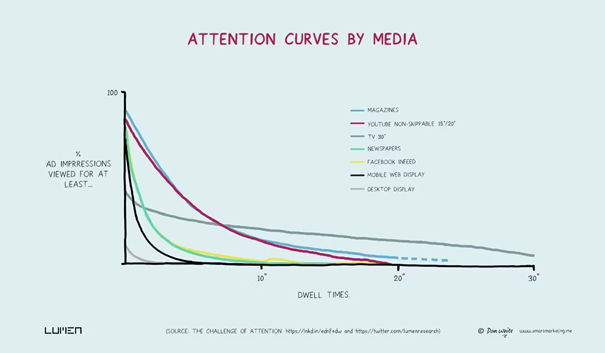

This said, most ads do not sustain attention for more than a couple of seconds. In his article Tom presents some data from Lumen (redrawn by the inimitable Dan White) which compares attention curves by media. Lumen state on their blog, referring to a similar chart,

"This chart shows the percentage of people who look for one second, or two seconds and so on – in total. They may not be watching from the start of the ad, and they may not be watching consecutive seconds: they may look at the screen, look away, and then look back."

Source: Dan White

Source: Dan WhiteCheck out the chart again (I believe this is the original version). Magazines, YouTube non-skippable, newspapers, and Facebook all get a high proportion of people attending for at least a second, but far fewer attend for longer than 2 seconds. One second is just long enough to figure out whether the ad is likely to be worth further attention.

By contrast, TV starts off with an inherent disadvantage. According to the Lumen data less than half of TV ad impressions are viewed at all. (I vaguely remember research from decades ago that stated only 1 in 3 campaign impressions on TV were viewed, so little change there.) However, the big advantage of TV advertising is that if someone is in the room when an ad breaks, there is a good possibility they will attend to some, maybe all, of the content. This is why Lumen finds that TV appears to be an attention bargain compared to other media.

Most ads just do not work well

While Lumen concludes that some attention is better than nothing, looking at the work done with Dentsu suggests to me that there is a time threshold before there is any sizeable uplift in recall or choice. Have a look at the chart for choice uplift, there is an uplift in the first few seconds, but it is reasonably constant, and only really increases after about 4 seconds. Given that most ads do not achieve the 2 second mark, let alone 4, that suggests to me that most ad impressions are falling short of their full potential.

This inference is consistent with Nelson-Field's finding that only 15% of ads gain enough attention to leave a lasting impression, and that percentage is remarkably similar to data I have seen for lead generation ads. Most leads generated come from a minority of ads. My conclusion is that whether it is generating a lead, sale, or a memory, most ads just do not work well. This is not to say they do not work at all, simply that most ads could achieve far more if they held people's attention for longer.

Learning curve?

That brings us back to the importance of creativity and why it is not implemented more widely.

In his article, Tom asserts that,

"We've had 70 years to learn how to make TV ads, but only three years to make TikToks. Of course we've not perfected this yet and of course we're only going to get better at it."

I guess this is where I must beg to differ. Unless there has been some dramatic uptick in TV advertising effectiveness in the last couple of years, all the evidence I have seen suggests we are just as bad at leveraging the power of creativity for TV ads now as we were 70 years ago. I suspect that most of the difference between TV and TikTok can be ascribed to the nature of the platform, not the practice of advertising on that platform.

Beyond anecdotal evidence

Tom claims that brands are learning and calls out a couple of TiKToks as evidence, but that is a bit like holding up IPA Effectiveness Award winners as being representative of advertising practice at large. Of the thousands of campaigns that run every year, few case studies are entered for the IPA awards, and fewer still actually prove their effectiveness and win. Yes, these examples demonstrate the true power of advertising when executed properly, but they are the exception not the rule. Applying the same logic to the assertion that platform-native creators are really the answer to creative effectiveness, I must ask whether his examples are among the 15% of TikToks that manage to get more than 2.5 seconds of attention, and which then get ruthlessly promoted by the algorithm to reach more people who might appreciate them?

Why are we not better at leveraging the power of creativity?

All this brings me back to the question of why the basic principles of effective advertising are still not being practiced.

Why does the advertising industry seem to be learning averse?

Is it simply that they see creativity as the end goal, not applied creativity?

What barriers prevent brands from leveraging the power of creativity?

Answers in the comment box at the end of this page please.

Source: asknigelhollis.com